No new bills is a threat? Jones Act. Bondi in hiding.

No new bills – please!

The president has threatened not to sign another bill until the congress passes the SAVE Act. This may be the best news I have seen this year. Earlier the president threatened to implement the SAVE Act all by himself via executive order. But A federal judge in 2025 blocked that attempt that sought to require proof of citizenship for voter registration. Of course, the president actually doesn’t have to sign a bill for it to become law. If congress passes a bill and Trump takes no action for 10 days while the congress is in session, the measure becomes law without his signature. So what the president needs to do is say he will not sign a law and if congress passes one, he will veto it. I have a modest proposal: why don’t we declare the rest of the month “new law-free March?” Recall Gideon Tucker’s famous saying: “No man’s, life, liberty or property are safe while the legislature is in session.” That was true when Tucker said it in 1866 and it is true now. So please, please, please (to quote James Brown) Mr President, NO NEW LAWS!

The only way to pass the SAVE Act is to dump the filibuster. The republican leadership is loath to do so even in the face of mounting pressure from the president. Senate majority leader Thune knows that once you open this door then all sorts of mischief can happen – although he probably thanks Harry Reid for lifting the filibuster on Supreme Court nominees, else no one would ever get confirmed in this fractured political environment. But the breaking news is that John Cornyn is showing his desperation to get reelected and has had a miraculous epiphany and now supports ending the filibuster in order to get Trump’s endorsement in his race against Ken Paxton.

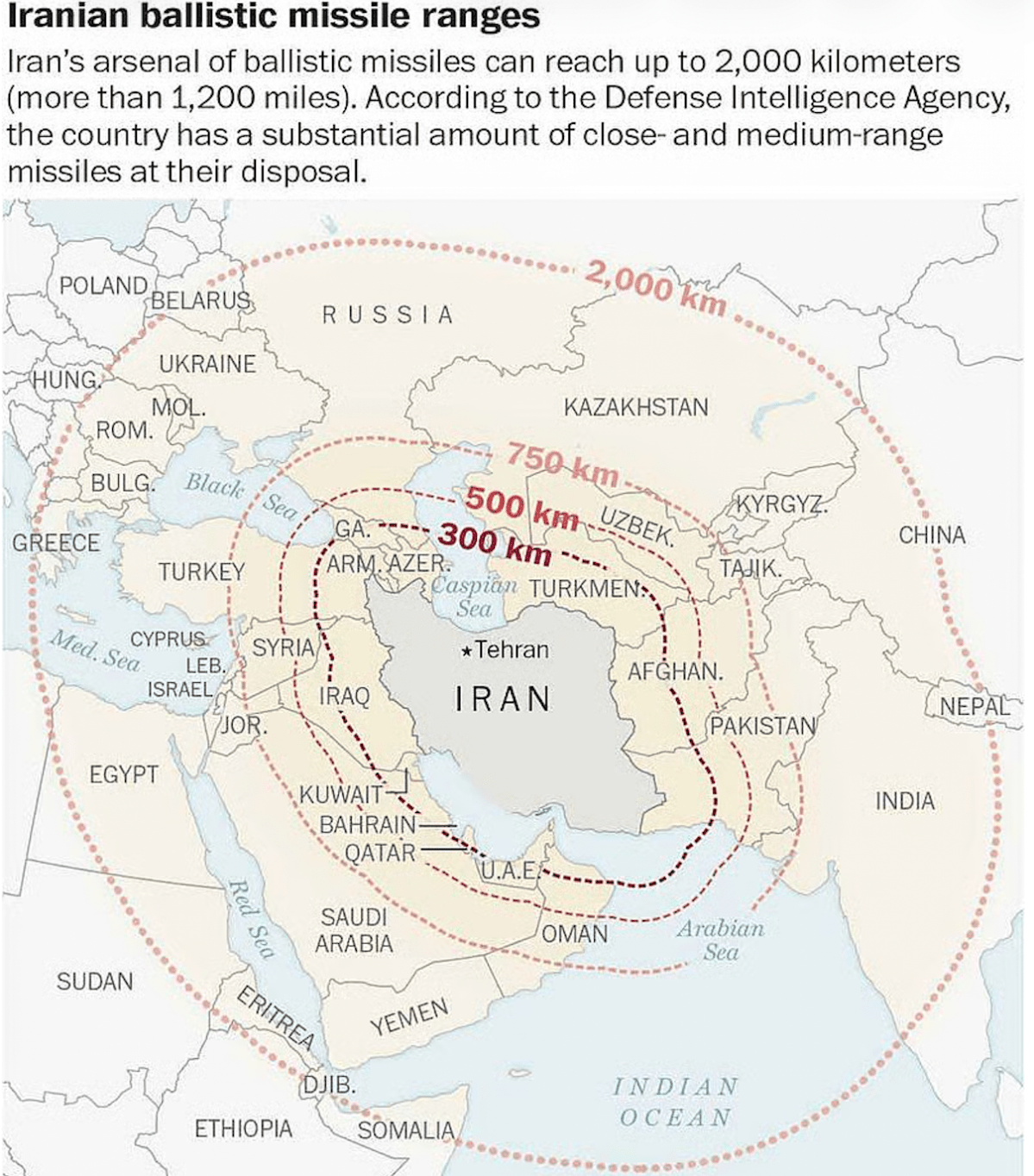

Repeal the Jones Act

Hawaii has the second highest gas prices in the country – or should I say out of the country. Sounds reasonable given that it is an island and all their oil must be shipped in. California is first due to all the silly rules and high taxes. But Hawaii even with its own brand of leftwing politics could see lower gas prices just by getting an exemption from the Jones Act. This is an act that Trump probably loves. It mandates that anything shipped from one US port to another must be made via a US built ship that is US owned and crewed. The act – formally the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 – is pure protectionism. It was intended to protect American ships from foreign competition. It also was to protect American shipbuilders. To put it mildly, the act failed on both accounts. American shipbuilding is in the tank and the American fleet is pitifully small. There are hardly any US flagged ships. There are only 92 Jones compliant US ships and 55 are oil tankers. There are 93 other US flagged ships but they are foreign built and are therefore non-Jones Act compliant and cannot carry cargo between US ports. Isn’t this stupid? Only the 55 can transport oil between US ports but again the cost of transporting oil from a US port to Hawaii is more expensive than shipping it from a foreign source. It costs more to ship oil on US tankers from the Gulf to Hawaii than from the Middle East to Hawaii. To deliver gas from say the Gulf of Mexico or Alaska to Hawaii, it can only be done on American ships. The result is that all Hawaii gas gets shipped from foreign ports on foreign ships.

American shipping is in decline because all the costs, environmental laws and regulations make building a US ship five times more expensive that one built in China. Also U.S. ship operating costs are estimated at nearly 3 times foreign costs. So it is cheaper not to build the ships in the US despite the Jones Act. Why Hawaii isn’t exempt from the Jones Act has long been a mystery to me. BTW, the same applies to Puerto Rico. Why not just repeal the darn thing?

Bondi in hiding?

Attorney General Pam (Blondie) Bondi has move into a nondisclosed military base housing. Bondi, along with Secretary of State Rubio, Trump advisor Stephen Miller, Kristi (ex-border Barbie) Noem and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth now live in military housing somewhere in the DC area. I don’t know where but I am certain we are not talking about barracks. All are doing so for security reasons. Apparently the administration is taking seriously threats against all of them. I am somewhat surprised that this is not true for some of the Supreme Court justices as well. When I was in DC, at least three justices lived either in or near my neighborhood. We all knew where they lived and sometimes there would be a picket or two outside their homes. Recall the threat on Justice Kavanaugh? I presume that these homes are now being protected by law enforcement. So one asks “Why can’t the same be said for Bondi and the other Trump officials? BTW, I don’t recall this happening during other administrations.

Its Spring Break

It is spring break. When I was teaching I hated spring break and lobbied unsuccessfully that instead of spring break we just shortened the semester by a week. For me spring break was a disaster and would undo all the hard work of getting the students used to my demanding style. I would force them to participate, write papers, take essay exams with no aids (no cellphones, no laptops allowed). Then they would go off to the beach, drink, party and who knows what else. They would come back to class all tanned and mellow and have no desire to think about present value, strong form efficiency or asset pricing models. Attendance was terrible and attitudes were worse. Maybe the solution was that if I couldn’t get spring break cancelled maybe I should have gone to the beach too.